Best Practices for Data Workflows in Ag Science

I was struggling with the data set. The first 50 rows were summary stats (…I think), and then the actual data started. The file was over 250 columns wide, composed largely of phenotypic traits. Perhaps one third of the columns were unique variables gathered over several years, but, the variable names were inconsistent across years. Actually, there was no information on the variables, what they were measuring, and what scale they were on. The closest hint was a pattern of color coding applied to groups of columns: yellow, green, blue. There appeared to be partial duplication and/or combination of of some columns, but we could not reconstruct exactly what had happened to the data. No one could recall the full history of the file, what that color coding meant, who had pre-processed data, or what they had done. We did know that the raw data were long lost.

This was the not the first nor the last messy data set with an unknown history that complicated my capacity to organize and analyse the information.

Other problems I encountered with poorly managed data sets:

- Date sets with outliers removed based on individual’s researchers assessment on what looked weird or not.

- An Excel file several thousand lines with miscellaneous comments added every so often indicating a data point may be suspect.

- An Excel file several sheets wide of the same information across different years - yet the column names did not match, and some sheets included summary stats for groups of data, using empty rows to differentiate groups (again, I think this was what going on…).

There’s no way to sugarcoat it: management of raw experimental data and the analysis workflow is largely abysmal in the agricultural sciences, my academic home for 14 years. The process of cleaning, rearranging, filtering and preparing experimental data for downstream analyses is poorly described, if at all, in most papers. As many of know, much of data conditioning and preparation is done by students and technicians with little formal guidance or documentation of their work.

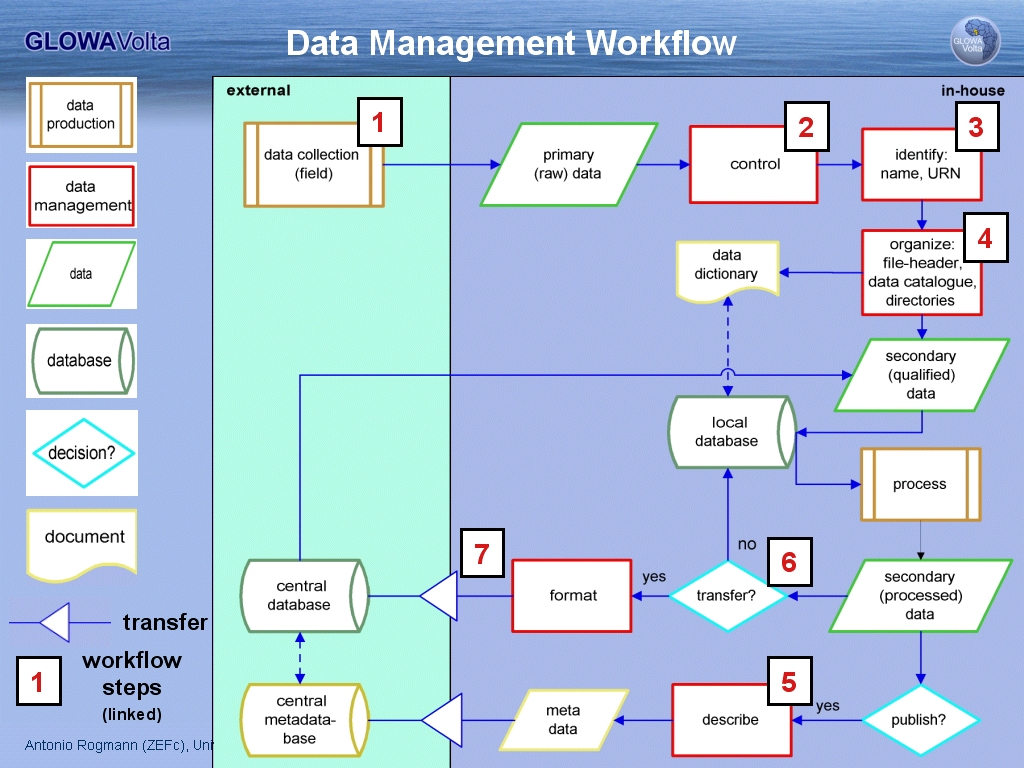

Since data sets can and should live on for decades - as part of long-term agriculture research, for meta-analyses or other uses, understanding how the raw data were parsed, cleaned and interpreted is important. Assumptions that made sense in the initial analysis may need re-evaluation later. Intermediate files can turn out to be useful. Organization of an analysis workflow can help researchers conduct their research in a regimented and reproducible way.

Here are a few concrete recommendations for improving workflow:

- Archive the raw, unaltered version of data set.

- Create a consistent directory structure for each project - that way you are storing things consistently and can find them. Really, this makes things easier for everyone.

- For a data set, each column should be include only type of data corresponding to the column name. These data can be on different scales. For example, if one column indicates the type of variable (e.g. pH, moisture content, nitrate concentration), another columns could indicate the actual value for that trait and observation. It is less confusing if a column only contain a similar type of data (e.g raw OR transformed OR mean value), not data and summary stats together.

- Avoid use of formatting that cannot be interpreted as plain text. By this, I mean do not insert comments in Microsoft office files, or use text formatting tools (bolding, color coding) to differentiate observations. This information can easily become lost to time and does not translate well to other software, especially command-line software. Comments, categorical variables, et cetera should each have their own column.

- Summary stats of a data set belong in their own table or file.

- Use a non-proprietary format like CSV or TXT.

- Avoid creating data that relies on a particular order of the observations (for instance, every 5th row is the mean of the previous 4 rows). One sorting step can ruin this. If a special order is needed, create a column which implements this.

- Make a “codebook” documenting what each variable means, what scale it is on, expected levels or range of data. This can be one sheet of information - very brief, but handy. Giving variables short, descriptive names is also helpful.

- Document what happens to a data set - and make that information available to others. I prefer to use a command line tool like R, but a text file could do. This is to ensure your work can be duplicated. I realize programming is not for everyone, but using a command-line program like R, Python, Julia, SAS, or even bash, is one of the best ways to document how information is pre-processed. Changes made through point-and-click interfaces like Excel are not reproducible because they are almost always incompletely documented or not documented at all. In addition, manual manipulation in a spreadsheet program also results in user-generated errors: misspellings, misclassifications, cut-and-paste errors and so on.

- Accountability and follow up: attach people’s names to their data and/or analysis.

- Back up your data: across at least 2 locations over the life of your project. Version control make it possible for your work to be undone by accessing earlier versions. Git is one such tool, but saving intermediate file versions (often!) can also help. By providing descriptive comments at each new commit (a version), that can help downstream researchers sift through previous versions of the data. Also, some cloud storage providers (like Dropbox) offer options for data recovery.

- Coordinate with project collaborators regarding workflow expectations and processes

The core reason I am interested in these issues is to improve reproducibility. As I dealt with the aforementioned issues with data, I could not help but wonder if I was making the right choices with the data, and wish that I had more information on the background of these legacy data sets. This is particularly important as meta-studies continue to gain in popularity. Unifying data sets and leveraging their combined power is one of the priorities for agricultural productivity identified by the National Academy of Sciences in their recent report, Science Breakthroughs to Advance Food and Agricultural Research by 2030.

For more information, see this excellent article by Kara Woo and Karl Broman - it’s short and gives easy-to-follow best practices when working with spreadsheets.

Scott Long at the University of Indiana put together an informative set of slides delving further into the principles of data workflow. Patrick Schloss, of the bioinformatics program mothur, recently published an article delving into the problem of reproducibility in microbiome work and how to fix it. Among many things, he recommended implementing robust workflow practices.